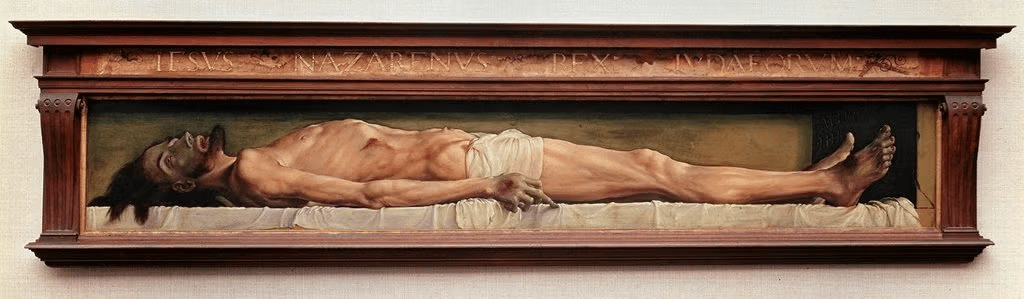

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (Hans Holbein)

In The Idiot, Dostoyevsky stages the ultimate contradiction of faith through the voice of the terminally ill Ippolit Terentyev, whose “necessary” suicide transforms mortality into protest. Within his lengthy explanation, the nihilistic Ippolit declares a mutiny on Prince Myshkin’s Christian beliefs: if existence is God’s gift, then self-destruction becomes its rejection. Dostoyevsky himself, a devout Russian Orthodox, saw Christ as the embodiment of absolute beauty, and Myshkin as His human reflection, the incarnation of purity and compassion. Whereas Ippolit, a self-proclaimed nihilist, represents the religious doubts that troubled the author. In his fevered speech, he turns the act of dying into an aesthetic performance of defiance. This essay explores Ippolit’s paradox chronologically through the three movements of his declaration. The analysis of each movement weaves in Dostoyevsky’s broader theological experiment, the context of Orthodox ideas of kenosis, and explores the echoes of the moral weight from other religious thinkers such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Camus — demonstrating how in rejecting the divine order, it consequently professes its necessity.

The monologue opens as a performance, Ippolit insists on reading his confession to a reluctant audience, turning the act of dying into theatre. It echoes Bakhtin’s notion of the carnivalesque confession; speech that asserts the self even as it collapses into contradiction. He denies life’s value, yet his desire for listeners exposes a hidden will to extract meaning. The monologue oscillates between sermon and suicide note, where his own reasoning to deny the divine sounds like transcendence. His first reflection treats life and death as a single continuum. When Myshkin invites him to spend his last weeks “among the trees,” Ippolit calls it a provocative invitation to “die” among them. For him, the stillness of the trees is cosmic indifference. In Orthodox theology it would be constancy. Dostoyevsky turns this misreading into an inverted Eucharist in which communion finds itself with decay rather than renewal. What faith sees as mystery, Ippolit swears is futility.

When Ippolit insists “it’s not worth telling lies for two weeks” he is aware of his contradiction and the vanity of his nihilism. That any dogma, any system, implodes when faced with self-reflexivity. By secularising paradox, it becomes emptiness rather than the mystical. Thus, he misses Dostoyevsky’s larger theological irony of incoherence being precisely where faith begins. His failure to maintain consistency demonstrates that human logic fractures at the threshold of the divine. When he admits that pain from torture would make him cry out, it shows that truth must pass through flesh. Christ’s passion is the ultimate joining of spirit and body and Ippolit’s inability to endure pain is a fallen inversion of that union. His reason remains disembodied therefore unredeemed. When the nihilistic doctor diagnoses him with consumption, Ippolit suffers from the lack of having someone to argue with. He wants despair to be singular, not clinical. Sartre later described the Other’s gaze as annihilating freedom; it is the foundation of a typical rebellion’s narcissism. The need for a personal revolt, with reflection being the highest offence. His insurgence falters as his own mortality offends him.

The nightmare of the Death Creature begins this second movement. The scorpion that terrifies him recalls Ippolit’s later shock before Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. Both images confront divinity through decomposition, Christ’s body rendered in rigour mortis, the creature embodying life that kills. In Orthodox belief, creation holds both life and death within it; for Ippolit this duality is cruelty. Curled beneath his blanket, he mirrors the painted Christ—motionless, human, transfigured. Ippolit’s gaze freezes at the speed of the creature, it’s the velocity of morality itself. When his dog attacks, the scorpion stings its tongue, showing that death triumphs regardless of bravery or defeat. The dog fears instinctively but doesn’t question meaning. Whereas human consciousness grants no reprieve but only multiplies terror.

His interrupted confession repeats the same drama in social form. Laughter from the guests turns his rebellion into humiliation. It stages the failure of communion, a true confession requires a listener, but Ippolit’s bored audience mocks him. The fury at being ignored exposes a paradox; he denies meaning but craves validation. The scene resembles Christ’s cry of abandonment but emptied of faith. Camus called this the absurd, the mind demanding coherence from a silent world. The refusal of the crowd also mirrors Nietzsche’s later image of the “madman” shouting that God is dead and being laughed at in the marketplace. The yell does not long for agreement but for resistance strong enough to prove that meaning still exists. Ippolit continues on by saying that there was “no reason to read with six months left”. This creates an epistemological contradiction: if all knowledge perishes what is it worth? Yet his very reasoning proves the vitality of intellect even in decay. It anticipates Camus’ absurd logic that we seek coherence knowing it will die with us. Ippolit’s despair proves the persistence of metaphysical longing, only a creature conscious of meaning could grieve the loss of learning.

He goes on by saying the “walls” are dearer to him than the prince’s offer of “trees”. The wall is certainty built by the self, a retreat from divine openness. Where Orthodoxy asks for kenosis, self-emptying into God, Ippolit seals himself within his own limits. A Luciferian impulse to define the cosmos by self, rather than by grace. In apophatic theology, silence affirms the divine. For him, it denies it as he mistakes incomprehensibility for non-existence. Dostoyevsky turns kenosis inside out: the soul emptied not toward God but against Him. Ippolit believes his idea is too complex to be understood and is insecure about his expression. This meta-level anxiety completes Dostoyevsky’s experiment that meaning disintegrates the moment it seeks articulation. The inability to express the infinite becomes proof that the infinite does not exist.

In the third movement, his anger is a remnant of faith inverted, proving that the soul cannot fully detach from the life it condemns. Reality “hooks” him back to life, even his nihilism cannot suppress instinct. This tension between thought and action recalls Camus’s “daily revolt,” the human will to act even in the absence of meaning. For Dostoyevsky, that instinct is not revolt but grace, the same motion of life that creation itself embodies. Ippolit calls it temptation, an inverted asceticism that seeks freedom from grace rather than from sin. His nihilism takes a turn for moral sadism as he blames others for their own suffering to validate himself. Dostoyevsky’s irony here is that the self-proclaimed nihilist becomes the harshest moralist. It is the antithesis of Christ’s compassion, he weaponises suffering to prove a theory. When a neighbour’s infant freezes to death, he smiles and blames the father, but guilt follows. Compassion returns unbidden, violating his theory. Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’ flickers here as parody: Ippolit’s self-assertion depends on the very moral framework he denies. In scorning the weak, he reenacts the world’s fallen cruelty; his judgment of others mirrors the divine judgment he rejects.

When he encounters a poor medic in crisis, Ippolit decides to help him out. To do so, he reaches out to his charming ex-classmate whose easy virtue he resents. After it’s successful, Ippolit offers a rare moment of insight “whoever attacks individual charity attacks the nature of man”. In helping the medic, Ippolit briefly articulates the principle of Christian personalism: grace transmitted through human contact. After envy of his ex-classmate poisons it; even charity becomes another stage for self-worship. He says that helping others is like “sowing a mighty seed”. The seed metaphor reflects the temporal modesty of moral action in never being able to see the full outcome. The idea of continuity is recognised but detaches from transcendence, turning it into a secular immortality project. In Christian symbolism “the seed “is resurrection: “unless a grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies…”. He misreads the parable; he wants to sow an idea without dying spiritually first. The image recalls Kierkegaard’s “knight of faith,” who must first die inwardly to be reborn, but Ippolit cannot complete that private death.

His decision to die arrives as a “strange jolt,” an inverted revelation. What faith calls grace becomes the command to self-annihilate. The silent visit of the spectral Rogozhin mirrors God’s silence where presence is mistaken for mockery. Ippolit’s performance of confession turns repentance into spectacle, an anti-sacrament where language replaces grace. In claiming to stand “beyond judges,” he repeats Lucifer’s revolt in which freedom is defined as isolation. Orthodox theology calls that state hell itself.

The “Explanation” itself evolved into a performance. Originally conceived as a suicide note for the police, it transforms into a sermon against meaning that reveals his craving for audience and legacy. In Orthodoxy, confession purifies the soul through repentance. Ippolit’s is a reversion, a speech without contrition with justification masquerading as a revelation. It’s a ritual of isolation, turning language into an anti-sacrament by refusing forgiveness. He declares that mortality would have reproached him for suicide if he were in “good health”. Thus, this “Explanation” lets him balance justification between his body and the divine. Ippolit claims to be “beyond the power of court and judges”, that his moral laws are nullified by mortality. This is the Nietzsche’s impulse: the loss of transcendent order dissolving ethics. Orthodox theology holds that liberty exists only in communion with God, apart from that, it becomes exile. Ippolit’s self-declared untouchability mimics Lucifer’s fall, rebellion born from wounded pride.

Myskin’s idea that death might be “for the best” is ridiculed by Ippolit. It mocks Christian aestheticism where beauty redeems suffering. The “trees” and even the “happy housefly” become emblems of indifferent creation and even symbols of mockery of last days. In his parody of meekness, humility degrades into humiliation, yet the outrage betrays faith’s residue. Ippolit admits that he cannot imagine total absence. In rejecting grace, he reveals that divine love appears to him as insult to pride. Ippolit has the capacity to admit the existence of eternal life, however, refuses to obey what he can’t comprehend. It recalls Kierkegaard’s young thinker that initially “doubts everything” and ends up in despair. It’s a satire on the belief that “doubt” accommodates the quest for truth; momentary in thought rather than a painful human affliction. Tying back to the Holbein painting, it was unfathomable that disciples looked at Christ in that grim state and believed in resurrection. In Orthodox mysticism, the divine surpasses understanding but still commands worship. Dostoyevsky’s paradox is that the intellect believes, but the will rebels. Ippolit’s tragedy isn’t disbelief, but faith stripped of humility.

Ippolit’s final act mirrors Adam’s disobedience of asserting autonomy through destruction. Camus called suicide the only serious philosophical question, for Ippolit is it is the only form of agency left. A false freedom and a metaphysical protest against creation itself. His declared suicide, framed as free will, is a last protest against creation’s “ridiculous terms.” The mutiny itself goes against every principle of nihilism, where nothing should matter not even the gift of the Creator. Thus, there’s nothing to rebel against. Ironically, the protest collapses at the moment of execution where Ippolit fails to pull the trigger. The gun misfires, and his failure exposes the ultimate irony of his revolt in which death itself refuses him. In this ultimate humiliation, Dostoyevsky resolves the paradox in concluding that the human will cannot abolish creation because even rebellion depends on the breath it seeks to end. Ippolit’s unfulfilled suicide becomes an unwitting confession of faith; in denying God, he proves that existence cannot be escaped, only endured.

Leave a comment